Iconic Representation – Notating Student Compositions in the General Music Class Setting

In those first years of teaching I tried a variety of composition projects. Each one was laboratory like, as if the general music class was its own entity, separated from the ways of being in the real musical world. I expected the students to know how many beats were in a quarter note, half note, whole note, etc., creating composition assignments that would assess them somehow on note values while giving the air of an authentic process of composition. The assignments were sterile.

This was before the world of iPhones, iPads, and apps, there was no drum groove playing in the background the way there is now in our classes. Compositions were done in a group, which was problematic on many fronts. A few students did all the work, while the rest were merely along for the ride. Assessment became an issue. Higher functioning students unfairly lost points when the overall composition was deficient in some way, due to a lack of work by their teammates. Today, all assignments in the general music classes at HA are done individually. In this way all students are held responsible for demonstrating an understanding of each concept.

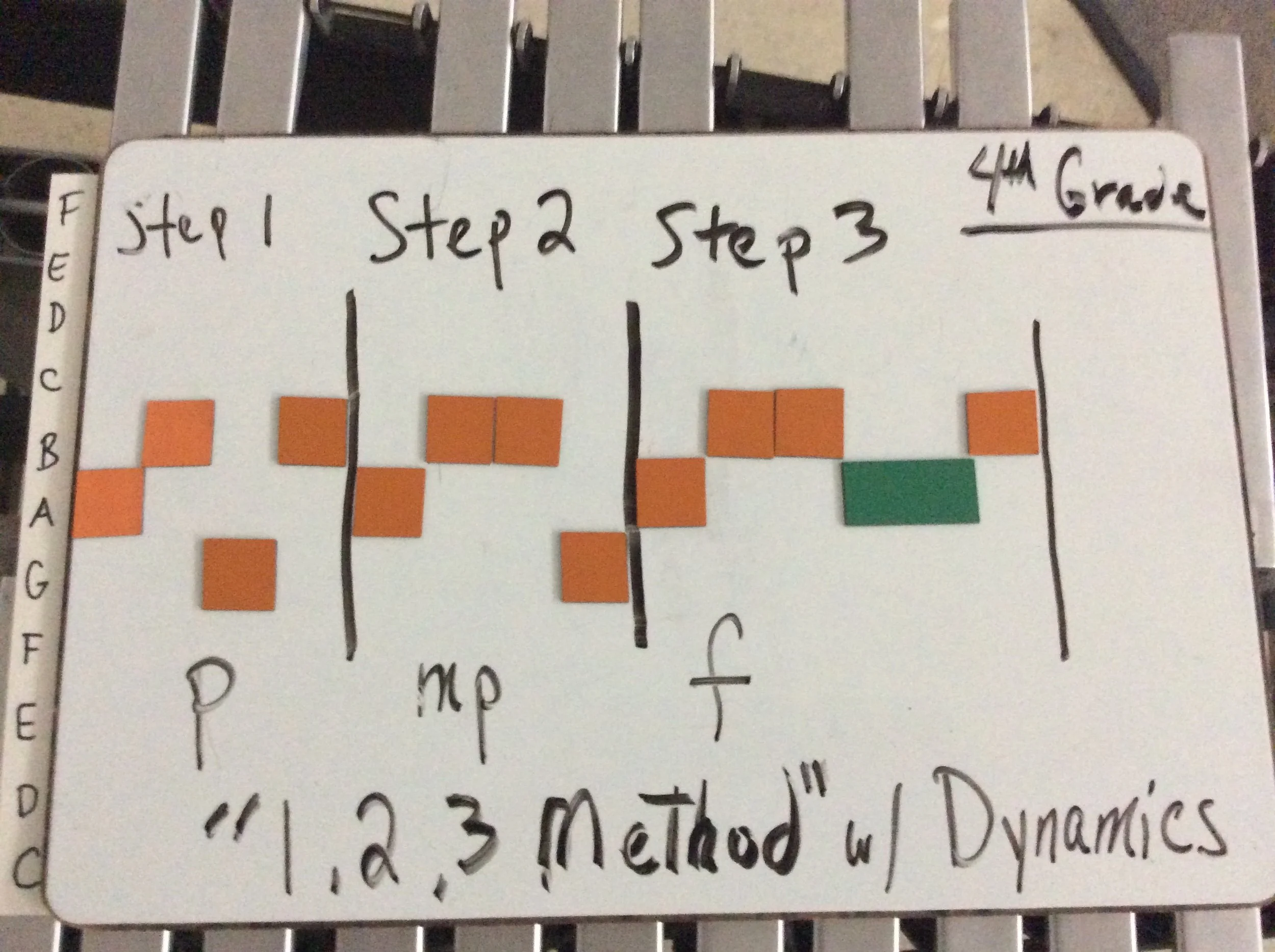

Getting back to the problem of notation. During my graduate studies at Oakland University (OU), we had discussions about the use of notation in the general music class setting. After learning about iconic representation, I made the decision that I would no longer use standard musical notation for 4th and 5th Grade general music classes. This would allow the students to focus on authentic musical processes without getting bogged down with what Jackie Wiggins called, “our secret society of music handshake.” Notation is part of the 3rd Grade General Music curriculum for six months when the students learn to play the recorder. This is an introduction to standard notation in preparation for the Beginning Band program for 4th and 5th Graders. My rationale was, if the students wanted to continue to study notation that would come with the band program, or I could easily differentiate instruction for students who wanted that.

The general music class instead would focus on authentic musical processes of creation. Without the focus on standard notation, I felt the curriculum could cover more ground. Iconic representation, as it was presented to me during graduate school, was a way of representing the pitch or highness and lowness of a note along with its duration. Initially I was using a set of magnets on the board for each song I was teaching. At that time, iconic representation had nothing to do with student composition work. I was searching for a way for students to represent the notes in their compositions. Most students would write down the notes on a piece of paper. Rhythm was pretty much left out. Over time, it became more apparent not having a system for the students to notate their compositions was a problem, and I didn’t want to go back to standard notation. I see students twice or three times a week for a half an hour. It felt as though all too often the students had to go back to square one, because their notes didn’t allow them to replicate what they had already composed.

The first solution I had was to cut slips of colored paper that corresponded to the icons or magnets we had been using when learning to sing songs. These pieces of paper were different sizes, just as the icons were. The students then glued them onto a piece of paper that had letters going up the side to correspond with the notes on the instruments they were using (Orff xylophones, keyboards, marimbas, vibraphone, or steel drums). I used this system for two years, but it had its limitations. When I helped make corrections to student compositions, pieces of glued paper off had to be peeled off, making a mess of their work. In general, it made revision difficult.

Eventually, I came up with the idea to have white boards and a set of magnets for each student. The issue then became the cost. I settled on 18” white boards. That was as big of a size I could find. With the size magnets I would cut, this would allow for a four-measure phrase with a couple inches left over. The students each had a set of magnets, I would cut from a roll; 16 one inch orange magnets (quarter notes), 8 half inch yellow magnets (eighth notes), four two inch green magnets (half notes), and two four inch blue magnets (whole notes). My boss was very supportive of the idea, and paid for 30 sets of white boards and magnets. All told, I think this cost around $1000, maybe a little more.

Composition problems are designed for students to solve in one class period. When the student is done she or he takes a picture of it with an iPad. I now had a digital collection of student work. My next problem became how to store hundreds of pictures. I was using my own iPad to take the pictures. In a few weeks the amount of work was staggering. I began by uploading these to Microsoft’s One Drive. This proved to be a timely process, but I was quite satisfied with the direction this was going. The general music classes were running very efficiently. Students were creating a large body of original authentic work.

This past year I tweaked the process again to solve the problem of me having to upload all these pictures somewhere. I discovered the app Seesaw. Seesaw is a digital portfolio system for teachers. You set up classes and the students create individual accounts using their Gmail accounts. There are other ways to set up Seesaw for younger students who don’t have email accounts or if they are all using a shared device(s).

Again, my boss was supportive of this process, buying the music department an iPad. The students now compose the work to meet the demands of problems I pose. They take a picture of the work and record a video of themselves playing their compositions, uploading both of these to Seesaw. Seesaw allows for the student’s digital portfolio to follow them from year to year, so we now have an ongoing digital collection of original work. Seesaw is quite flexible. There is a free version that is limited to ten classes. I use the paid version Seesaw Plus, which gives me twenty-five classes, the ability to make private posts (only visible to teachers), record private notes on student work, and create ongoing skill sets based on the curriculum. Here are reproductions of actual student work: